Shane Guffogg: Color Essay 7

Women and the Abstract Expressionist movement making history

(Conversation between Victoria Chapman and Los Angeles based artist, Shane Guffogg continues)

Abstract Expressionist artist, Louise Nevelson

In Color Essay 6 we talked about women artists from the Abstract Expressionist movement starting with Helen Frankenthaler’s absence of color to the bold brushstrokes of Lee Krasner, and onward to Joan Mitchell who taught us how to see differently. Then there were the spiritual missions of Agnes Martin and Hilma af Klint. In Color Essay 7 we continue to explore the movement and talk about how these courageous women develop their own independent voice during this revolutionary period in art history.

VC: Women artists of the Abstract Expressionist Movement continue to move forward reinventing the pictorial plane. What is interesting is how abstract art became a viable medium to reveal these messages. Let’s talk about the work of Louise Nevelson (1899 – 1988), who came to the United States from Russia when she was 3 years old. Nevelson grew up in Rockland, Maine, and left for New York City as soon as she could to pursue a career as a serious artist. The energy and dynamics of the city mirrored her soul. There, Nevelson could feel the thrust of creativity with limitless boundaries and she had no fear in exploring it. The artist studied with Hans Hoffman in Munich as well as New York, and assisted Diego Rivera in 1933 with his mural, Man at the Crossroads, at Rockefeller Plaza. Her art career began with drawing, then experimenting with etchings and lithographs. Nevelson had early memories of walking along the coastal shore in Maine, watching for the objects and things that would wash up. These memories would revisit her in the big city, in the form of discarded materials that were left along the streets. As hard times approached, one night Nevelson and her son walked along these same streets, looking for wood to take home and burn to stay warm. Over time this task became a conscious effort that made its way into her art practice. The ritual of collecting odds and ends and sanitizing them to become pristine objects made a permanent entry into her work. By this time, she had begun working in sculpture. Nevelson’s puzzle-like, sublime, and sensual sculptures came to resemble drawings. The shadows cast by her found objects as they rested against one another in various and specific arrangements took on a profound presence. Often Nevelson worked in monochromatic colors: solid black, gold, or even white. What do you have to say about Louise Nevelson and her sculptures; why does the use of one, solitary, color work so well? Do you think the outlines present across her sculptures’ faces fall into the category of drawing?

Louise Nevelson, 1960-4, An American Tribute to British People, painted wood, 122.1 x 174 x 36 in.

Louise Nevelson, 1976, Bicentennial Dawn

painted wood, 180 x 1080 x 36 in.

Shane Guffogg: Anytime monochromatism is utilized within art, the nuances and spaces created by colors are broken down into shapes and forms, thus becoming an object rather than a subject. The items Nevelson used began as subjects, as they represented things from her own past. These subjects, such as found pieces of wood or old parts of broken furniture became objects when they were taken out of one context and put into another. Because we can recognize some of the shapes she chose to use, her works, especially the all-black pieces, become like memories of memories – they tug at us to open up, allow ourselves to recollect moments that are buried deep within our psyches. And yes, the shapes she uses and the way that light catches them are very much like drawing (especially like drawing with a gray pastel on black paper). Whenever I see these works, they always make me think of machines. The flat black that she used is the color of charred wood or cast iron. These 3D paintings become strange artifacts, almost like discoveries from archaeological digs. Are they machines from a distant past? Are they the fragments of a society that has collapsed, leaving us with unanswerable questions about what happened to its people? Black is the absence of light. Her works, especially larger pieces like Mrs. N Palace, are confrontational. They stand like monoliths that were blown apart, but then put back together by another culture, unaware of their original forms, leaving them as strange, architectural moments to ponder.

Louise Nevelson, 1979, Moon Zag III

painted wood, 25.5 x 28 x 7.75 in.

Lee Bontecou, 1962, Untitled, soot on paper, 10 x 13 in.

Shane Guffogg: I was fortunate enough to see her retrospective at the Hammer Museum in Los Angeles and The Chicago Art Institute in the early 2000s. It was really interesting how the layout of the museums changed how the art was curated and displayed. Regardless, it was a powerful exhibition that left me feeling that I had just witnessed something quite profound. The works from the late ‘50s and early ‘60s were so powerful. The 3D wall pieces were invasive, jutting out from their canvases like thoughts that had replicated into a condensed machinery. They consisted of welded steel structures and found canvases and tarps sewn onto steel rods as if an organic object had been blown apart and someone tried to piece it back together (Nevelson-esque). The colors, or lack thereof, harkened back to the early cubist works of Picasso and Braque, devoid of rich colors like red and blue – they were awash in bleached earth tones. The surfaces looked like cubist paintings that had been pulled out from their canvases by a few feet, creating a topography that resembled the opening of a volcano. The works were so masculine that they felt almost dangerous in appearance. The canvases were stitched to their steel frames with wire, protruding outwards like cactus needles. These works felt like the aftermath of a devastating war; pain and suffering sewn together by damaged hands in an attempt to hide what had been destroyed. As she was making these deeply emotional works, the mainstream art world was championing Andy Warhol, who was making paintings of soup cans. Bontecou’s later works were more colorful and whimsical; she began drawing star constellations, fish, and eyeballs, which makes me wonder if the dark openings in her earlier sculptures were meant to be pupils? Her fish were poetic, appreciating nature in all of its mystery, as were her constellations. Seeing her life’s work made me want to go back into my studio and give myself the license to follow whatever thoughts I had; to just trust my intuition. Her work was a melding of ideas, parts, and materials. It had the force of any great abstract expressionist art, but in its own, new way. In society, we all have roles that we are, more often than not, assigned at birth. The fact that Lee Bontecou welded and sewed, albeit with steel wire, was a brilliant way of crossing pre-described lines and defying boundaries.

Lee Bontecou, 1962, Untitled

welded steel and canvas, 68 x 72 x 30 in.

from 2004 Hammer Museum exhibition

Lee Bontecou, 1998, Untitled, colored pencil on black paper

1964, Lee Bontecou in her Wooster Street Studio

photo courtesy of Ugo Mulas

VC: Elizabeth Murray (1940 – 2007) was another artist that shook up the art scene; not only with color, but with the shapes of her canvases, too. I felt her work was as much about painting and composition as it was about music. Seeing her work in the ‘80s during my years at art school was a breath of fresh air. I think it is interesting that the women and men of this movement not only changed the pictorial field through the techniques of laying down paint, but also by slicing up the canvases, or, in other cases, (such as Nevelson and Bontecou) drawing with objects. Their three-dimensional works hung from the walls like paintings, but remained sculptures. Color and shape evolved. Of course, there were male artists that worked in black and white, like Ad Reinhert, Mark Rothko, and Gerhard Richter, but the way these women translated their post-World War II feelings is fascinating. Ruth Asawa’s (1926 – 2013) biomorphic wire sculptures are relative as well, I can see her shapes echo in some of your pattern paintings. What do you think led these women to turn to monochromatism and sculptural influences to transmit their art practice? What other artists from this period are you inspired by?

Shane Guffogg: I loved how whimsical Elizabeth Murray’s work was. Again, Cubism has fingerprints all over her work, but instead of flattening out the picture plane, she inverted it, bringing it out of the wall. As I recall, her early work was steeped in New York’s abstract minimalism, Möbius Band (1974, oil on canvas, 14 x 28 inches), being a great example of this. We get to see her thought process evolve as she asked questions concerning lines and form, space and color. I can almost hear her thoughts; “What if I take this line off the canvas? Where would it go? What if there is another canvas next to it to catch it? What if that canvas led to another canvas, which was more 3D, coming out from the wall? What should the shape of that canvas be? Ah, look around, what can I use? A coffee mug!”

I am, of course, projecting my own thought process here, but it is what I think and feel when I see her work. Murray added color – and lots of it – to her work, borrowing the saturated palettes of artists like Roy Lichtenstein, but she took her work in a completely different direction. I think the work of these last three women really pushed the envelope with what art could be. That is no easy task, but they did it.

Elizabeth Murray, 1974, Möbius Band, oil on canvas, 14 x 28 in.

Elizabeth Murray in her studio, 1996

Elizabeth Murray, 1979, Druid, oil on canvas, 54.5 x 56.5 in

Elizabeth Murray, 1983, 1,2,3, oil on canvas, 124 x 124 x 12 in.

Shane Guffogg: Ruth Asawa! I love her woven sculptures. I have only had the chance to see a few of them in person over the years, but each time I do, I stop and observe the visual poetry that breathes with silence; giving us small droplets of information, asking us to look around, to take in each moment, and know we are all part of this great mystery. Again, like so much of the art that I am drawn to, her work is not about the natural world, plants, the human form, or even language: it is informed by all of this. She became the translator, turning the invisible energy of the physical world (that manifests into plants and animals) into shapes that hover between our conscious and subconscious minds. They are pure in thought and form, transcending all of human history, suspended in a timeless state of being.

Close up of Ruth Asawa and wire sculpture

Ruth Aswa for LIFE magazine, 1954

Ruth Asawa, 1970, Untitled,

(SD.085, Sculpture Drawing: Tied wire with 8 branches),

ink on paper, 18.25 x 26.5 in.

Installation view of Ruth Asawa‘s “Life’s Work” at the Pulitzer Arts Foundation, St. Louis, Missouri, 2018–19. Photo by Alise O’Brien Photography. Copyright Alise O’Brien Photography and the Estate of Ruth Asawa. Courtesy the Estate of Ruth Asawa and David Zwirner.

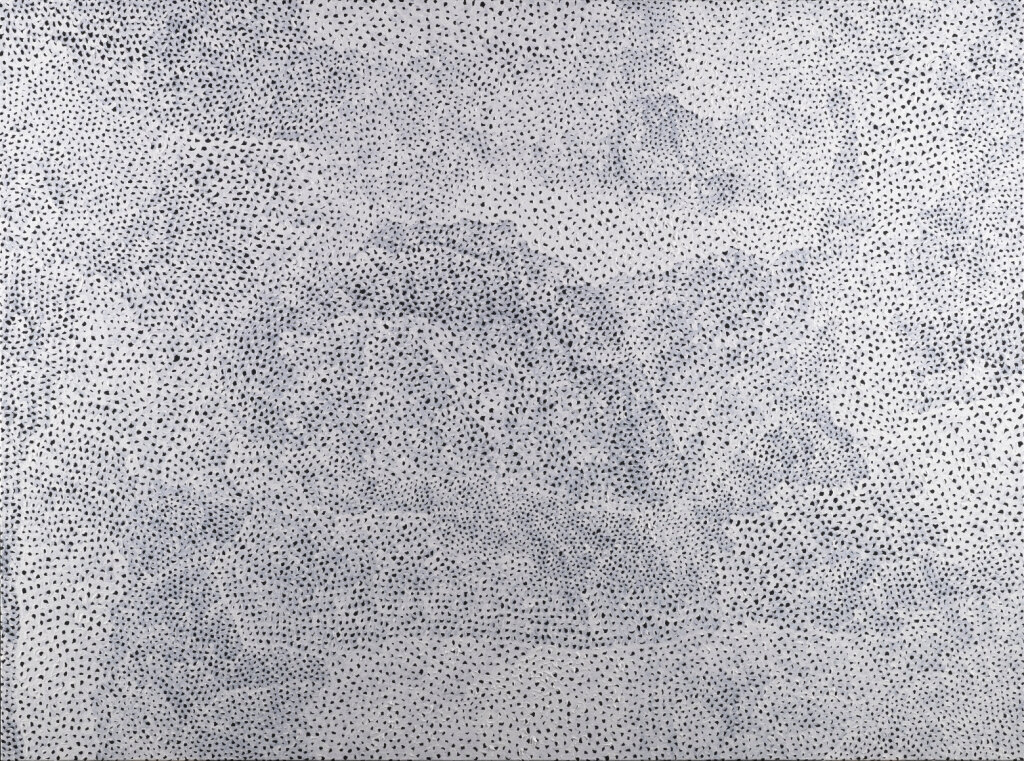

Shane Guffogg: And to answer your last question about other artists that come to mind, I would be remiss to forget Yayoi Kasuma. She is currently an art world star of the biggest magnitude, drawing record audiences to see her Infinity Rooms. I first became acquainted with her work from a single painting at LACMA, from her Infinity Net series. She painted the canvas one color, then painted another over it, leaving little openings; the work resembled a fishing net. Each opening appears to have its own gravitational field, pushing the top layer of paint away; from a distance these look like dots. These paintings pulsate with their own sense of energy, as if a thought was in the beginning stages of exerting itself upon our physical world. Like Asawa’s sculptures, they are pure in their purpose and exist outside of the art world’s gibberish. Kasuma took her Infinity Net paintings and translated them from canvases into environments; rooms illuminated by otherworldly lights, and mirrors which make them feel infinite; art that you can physically enter. People around the world wait in lines for hours to have the chance to walk into these rooms and experience her world vicariously through them. I read that she sees these dots everywhere, as if she is able to peer just beyond the human veil. Presumably uncertain of her own sanity, she checked herself into a mental hospital, decided to stay, and has had her studio across the street ever since. She is 91 years old now, still creating this ever-evolving thing we call art.

I think artists, and truly creative people in general, have some unknown element that develops over time, creating a deeper awareness of what is around them. They are more sensitive to their environments and the emotions that others are displaying. In some cases, that deep level of sensitivity makes the world at large too much to process. I could write a long list of creative people who would fall into this category, but their interpretations of life, in all its mystery, beauty, trials, and tribulations are what I am most interested in. I feel that is the role of the artist in the world; to witness and absorb all things and let those thoughts transform into an expression that illuminates, and in some cases, transcends our daily lives. All of the artists we have talked about in this Q and A about color do just that.

Thank you, Victoria, for giving me the opportunity to rummage through my own inner library and share my thoughts and observations.

Yayoi Kusama, Infinity Nets (FBB), 2013

Acrylic on canvas, 38 1/4 x 51 1/4 inches

Yayoi Kusama at an artistic “happening” in New York’s Central Park in 1969. Photograph courtesy of New York Daily News Archive/Getty Images

Yayoi Kusama, early Infinity Mirror Room

Yayoi Kusama, 1990, Infinity Net, acrylic on canvas, 28 x 35 in.

Yayoi Kusama, 1961, in front of one her Infinity Net paintings

(Freedom in Confinement)

Yayoi Kusama at work in her studio, in front of her painting The Moving Moment When I Went to the Universe. Photograph courtesy of: Yayoi Kusama Studio

Stay tuned for more conversations

Victoria Chapman

Studio Manager

A very special thanks to Neville Guffogg for editing.

Note: all images shown in this email are (fair use) public domain