Some artists spend countless hours – even lifetimes – drawing and painting from life, documenting their existence through physical forms and realistic subjects. Others create imaginary worlds based on abstract themes, all the while interpreting life in the way that they see it and feel it. Shane Guffogg is an artist that encompasses both factions, but also (from this writer’s perspective) creates an agent for the soul, taking the viewer on a journey to a spiritual realm.

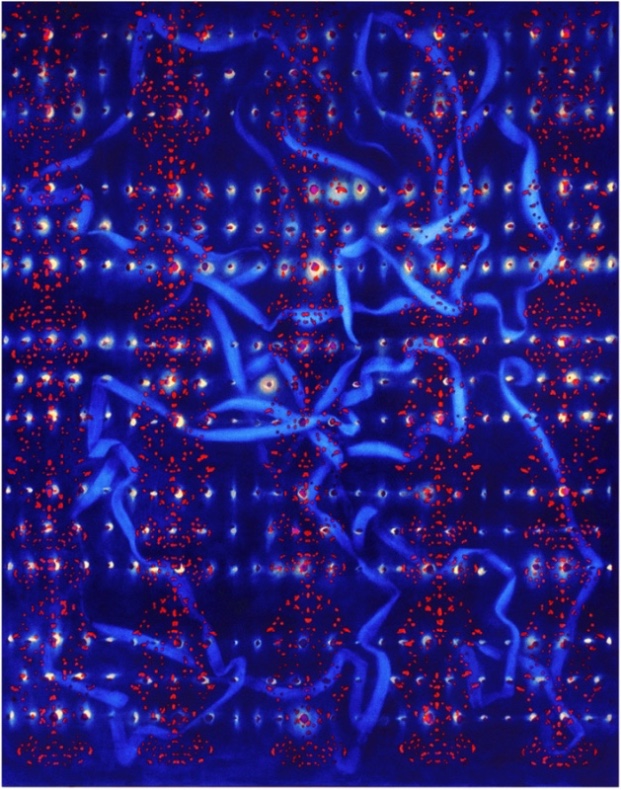

Guffogg shares a journal entry about Untitled #70, a painting that was based on the flight patterns from a radar screen at the Dallas/Fort Worth airport. The abstract shapes that represent the painting are gestalt-like, revealing much more than flight patterns.

“A few days before finishing the painting, I decided to turn over the torn image from the magazine and read what it was. I was assuming it would be a picture of some organism seen under a microscope, but it was the opposite. The image of a dark area with little glowing green elongated dots was the Dallas/Fort Worth airport radar screen during rush hour, and the elongated glowing dots were incoming and outgoing planes. It was not the micro but the macro. But, more importantly, I realized that, through technology, we were now seeing the world through a mechanical process and then interpreting the information. We had entered the age of second-hand smoke, where reality was second to an image or idea of reality. We were once removed from the actual experience of life. This realization made me acutely aware of just how important the arts really are. Art, with a capital A, is the eyes, ears, and mind of all of humanity, and without it, we are deaf, dumb, and blind. Art has a bigger purpose than feeding the artist’s ego or making someone rich for having the foresight to buy when the artist’s work was cheap. It has a bigger purpose than brightening up a room or going with the new couch or filling an arena of screaming fans. Art was and is the essence of who and what we are, and it has the capacity, when handled by a master, to transcend our everyday life and go beyond to an intangible and indescribable place. That place is where all is one and time doesn’t exist. It is the home of God, which is nowhere and everywhere. Art, the arts, are a tapestry of invisible threads that tie us to that intangible and indescribable place. The place that just is. And the purpose of art is to give us a glimpse, a sensation, that it is there, right in front of us, all around us, within us and, ultimately, is us. I can’t help but smile when I think of Descartes’s quote, “I think, therefore I am.” It all makes perfect sense. The ability to recognize one’s own consciousness is consciousness itself. The observer is the observed.”

Shane Guffogg working in his studio

There could be many reasons why Guffogg calls to the spiritual. Starting in 1980, the year he graduated from high school, the world was seemingly in an upheaval; John Lennon was shot by a crazed fan just steps away from his New York City apartment; Mount St. Helen’s erupted; and a new era was beginning that felt unhinged, as the threat of a nuclear war with the USSR and the US, led by Reagan, hung in the air like a dark thunderstorm. Shane Guffogg was 18 years old, and after having spent the summer traveling around Europe (via a Eu-rail pass) with his focus on seeing all the great masterpieces, was back in his hometown attending the local Junior college.

The potential events that were unfolding onto the world stage were the basis for the painting titled Broken Eggs. In this painting, we see a chess board on the left, but missiles have replaced the pawns. The hand, taken from Leonardo’s St. John the Baptist, is pointing upward towards the heavens, and written on the base is the term “Manifest Destiny.” The flag hanging from the index finger signals that the United States sees itself as the chosen country to win. An outline of a dove taken from Picasso sits on top of the finger. To the right is a face rising from the sea of sand with the right eye being replaced by the Soviet Star. In the background is a pyramid, representing the ancient history of mankind, with a peace sign on it, a sign that has lost its potency and now serves as a target. In the center is a pair of eyes looking into this picture, into the potential future. The eyes are that of the 18-year-old Guffogg, who wore wire-rimmed glasses at that time. His eyes and the plank of wood they hang from cast the shadow of the cross, evoking the symbol of Christianity, and at the base of the cross are victims of the nuclear fallout, with bodies inspired by Gericault’s The Raft of Medusa. In the sky, the sun scorches the earth while the storm clouds gather, and in the foreground are 2 broken eggs taken from the nursery rhyme:

“Humpty Dumpty sat on a wall, Humpty Dumpty had a great fall;

All the king’s horses and all the king’s men couldn’t put Humpty together again.”

The eggs were potent symbols for the future of the east and the west.

Broken Eggs, oil on canvas, 24 x 36″, 1981

Around the same time, Guffogg recalls sitting in an art history class and the subject for that day’s lecture being Kandinsky. “By the end of the class, I had a headache from looking at Kandinsky’s art. His paintings made me see and think differently. I had to find out why it was having such an impact on me.” This experience prompted Guffogg to visit the library, which he did often, but this time he was seeking answers. He checked out Wassily Kandinsky’s book, titled, Concerning the Spiritual in Art. This book would begin laying the foundation for what Guffogg considers the purpose of art. Kandinsky’s words prompted him to embark on his first foray into abstraction, using crayon on paper that interfaced with painted pieces of cardboard that were glued onto the paper. The crayon marks were done quickly and deliberately, to capture his ideas of cause and effect.

Untitled, cardboard acrylic and crayon on paper, 11 x 13", 1982

Untitled (green), cardboard acrylic and crayon on paper, 11 x 13", 1982

Untitled (yellow), cardboard acrylic and crayon on paper, 11 x 13", 1982

Every person has many pieces to their life that fit together like a puzzle, creating a picture. As I learn more about Shane Guffogg, I am gathering more pieces that give me a clearer and deeper understanding of what his work is about. For instance, while he was growing up in California's Central Valley, he was always close to nature, and because his family owned an exotic bird farm, he had little escape from the daily routine of farm life (albeit, taking care of thousands of birds). I can't help but wonder how stepping into the large aviaries filled with colorful birds flying around impacted his paintings. This farming community is nestled at the base of the foothills and dotted with farms that consist of citrus, olive, and almond groves, punctuated with open fields of cotton or corn, depending on the season. Again, this landscape, with the perfectly furrowed fields and aligned trees, creates patterns within patterns while driving by. It's not a stretch to see how this symmetry of man-made nature found its way into his work.

From a young age, Guffogg became accustomed to the long days of hard work. On a certain level, he could relate to the other farm workers, as the San Joaquin Valley was and still is a mass producer of the state's vegetables, fruit, and cotton. As he has said, farmers work with the clock of the sun, which means they put in long days. This upbringing had just as much of an influence on his life as did the books that fell into his hands. The connection between mind and body, the willingness to work and commit to work, the curiosity towards the natural world and man's place within it. It was no surprise that Guffogg would begin to contemplate the ideas of spirituality through his art.

The view outside Shane Guffogg's art studio in San Joaquin Valley

At the age of 18, he was learning how to see. Each painting, starting with his self-portrait as Rembrandt, opened up more possibilities of how to interpret the world, which dovetailed into his investigation of the unseen. Albert Einstein's theory of relativity explored the laws of gravity in relation to other forces of nature, and its effect on time and space. This topic nudged Guffogg to explore the cosmological and astrophysical realm: Quantum Physics. However, it was Kandinsky's view on the spiritual in art that gave Guffogg an opening to visually explore the ideas of meaning, emotion, and the human experience through colors, lines, and forms. During this time, his paintings were figurative, using the human body and still lifes as symbolic references to express his newfound ideas about how colors and shapes resonate with our emotions and can affect our psyches.

Self Portrait, oil on canvas, 36 x 24", 1981

At 18 years old, Guffogg injected his own face into one of Rembrandt's self-portraits

His compositions moved from colorful figurative paintings to paintings about his surroundings, like 1988's Sleep, which depicts 2 green pears, painted four times each, displaying the movement of light throughout the day, calling attention to the way we perceive the sun's rising and setting. Or 1993's Untitled #52, which is a 16-paneled painting of silhouetted wheat stalks; removing the context of nature, removing the connotation and denotation, creating, instead, a bridge between the physical and painterly worlds. The painting is embedded with a consciousness; a realization of the forms, from the representational to the abstract, derived through color, movement, light and even sound – a kind of existential dance to free the mind from implied meaning and unlock the soul.

Sleep, oil on canvas, 4 panels, 12 x 12" each, overall dimension, 261/2 x 16 1/2, 1988

Untitled #52, oil on canvas, 12 panels, overall dimension, 63 x 49",1993

In Kandinsky's book, Concerning the Spiritual in Art, he writes,

"When religion, science and mortality are shaken, the two last by the strong hand of Nietzsche, and when the outer supports threaten to fall, man turns his gaze from externals in on to himself. Literature, music and art are the first and most sensitive spheres in which this spiritual revolution makes itself felt. They reflect the dark picture of the present time and show the importance of what at first was only a little point of light noticed by few and for the great majority non-existent. Perhaps they even grow dark in their turn, but on the other hand they turn away from the soulless life of the present towards those substances and ideas which give free scope to the non-material strivings of the soul."

The passage inspired in Guffogg a need to reach deeper into comprehending the human spirit and creating a visual poetry that would serve as a conduit for a higher awareness. The artist had been on this path since 1981, but gained momentum through such works as 1995's Space Between the Breath, and 1995-2001's The Us of Me, made up of 3 panels. Each panel consists of concentric circles, and as they cross over into the adjoining panels, they become light sources that flow like undercurrents. Once the circles were painted, Guffogg spent years looking at and contemplating their movements, until one day he decided to do a drawing of the intersecting lines of light and then dark. These drawings would be used in a similar way as the wheat stalks from Untitled #52 – they were mirrored and flipped, becoming templates for the patterns that were evenly divided across the entire painting, creating a unifying picture of what lies beneath. One could also connect the dots from The Us of Me to the early crayon drawings. The sources of the patterns are the cause, and the patterns themselves are the effect.

The Space Between the Breath, oil on canvas, 56 x 58", 1995

Guffogg further wrote, in his journal,

“The title of The Us of Me was referencing my mother and father, with concentric circles on both sides feeding into the middle, and the circles in the middle feeding out to each side. It is about the connection that exists between me and my parents and the patterns that are created from these relationships. It is also about the inner connection of all things, all people. I started the painting in 1995 and was intending it to be the second companion painting to the triptych titled, I, which had concentric circles on the two outside panels. The circles fed into the dark hues made up of deep reds, phthalo green, and ultramarine blue of the center panel. For this newer painting, the idea of having the dark parts of the circle become the light source in the adjoining panels took the painting into a different direction. Once the circles were completed, I did a drawing of all the areas of the painting where the lines of light crossed. This became one of the patterns that was painted over the entire painting using a Naples yellow. Then I did a drawing of where the darker areas intersected – this became the red patterns. The patterns echo both the light and the dark elements of the painting, adding to the ripple-like effect of the concentric circles that move below the patterns. At that time I was deep into the Cannac series and was exploring the patterns that were created from images made purely from the subconscious. The Us of Me is a complex painting that explores how thought manifests into a visual realm, making the invisible visible. It is steeped in Western European Art History, with the depiction of light, as well as Eastern Mysticism, taking visual cues from both sides to create a new third element, much like adding a suspended major note to a chord while playing the piano. The painting took a total of 6 years to complete.”

The Us of Me, oil on canvas, 72 x 108", 1995-2001

Spirituality became a common thread in each work that he created, from the past to the present – there is always some sort of reference to the soul. This creative process is as important to him as life itself; to be seen, heard, and contemplated through his art. It is my belief that we are only just beginning to catch up.

The Russian avant-garde artist and visionary, Kazimir Malevich wrote this while conceptualizing his piece, Suprematist Composition, oil on canvas, (1916):

"In man, in his consciousness, there lies the aspiration toward space, the inclination to ‘reject the earthly globe’. ‘I feel myself transported into a desert abyss in which one feels the creative points of the universe around one.’”

Loic Gouzer once said, “Malevich pushed the boundaries of painting, forever changing the advancement of art and providing a gateway for the evolution of Modernism.”

Malevich’s words (which ushered in a new paradigm of thinking that was steeped in art as a portal to a spiritual awakening) now seem ironic when juxtaposed with the recent sale of his Suprematist Composition, which fetched $85.8 million on May 15, 2018. Maybe the record selling price is an indicator that the world is catching up to his ideas of art as a new way of seeing and thinking.

If Modernism was the process of adapting something to modern needs or habits, then from an early age, Guffogg was in the midst of creating an acute consciousness that would emerge from the operations of the brain. The artist did this by leaping out of the figurative mode and into the abstract picture field. From a young age he was already writing and playing music. As a self-taught musician, naturally, he made the connection. Kandinsky wrote:

“Something similar may be noticed in the music of Wagner. His famous leitmotiv is an attempt to give personality to his characters by something beyond theatrical expedients and light effect. His method of using a definite motiv is a purely musical method. It creates a spiritual atmosphere which precedes the hero, which he seems to radiate forth from any distance. The most modern musicians like Debussy create a spiritual impression, often taken from nature, but embodied in purely musical form. For this reason Debussy is often classed with the Impressionist painters on the ground that he resembles these painters in using natural phenomena for the purposes of his art. Whatever truth there may be in this comparison merely accentuates the fact that the various arts of today learn from each other and often resemble each other. But it would be rash to say that this definition is an exhaustive statement of Debussy's significance. Despite his similarity with the Impressioniststhis musician is deeply concerned with spiritual harmony, for in his works one hears the suffering and tortured nerves of the present time. And further Debussy never uses the wholly material note so characteristic of the programme music, but trusts mainly in the creation of a more abstract impression.”

Kazimir Malevich, Suprematist Composition, oil on canvas, 34 7/8 x 28", 1916

Sold for $85.8 million on May 15, 2018, at Christies, New York

Shane Guffogg's snapshot of Wassily Kandinsky's painting while visiting the Hermitage Museum

Shane Guffogg playing guitar, the artist has written over 300 songs

Guffogg continues to be present; searching, listening, and examining the eternal truth of our existence. He writes another journal entry (while sitting on a beach on the Greek island of Paros) about light and the universe and the immediate connection we have to all things:

"One day as the sun was setting, I was the last person still sitting on the beach. The colors that were dancing off the water were changing by the second, first from white and light blue, to yellow and pinks, then to orange, as the sun looked like it was sinking into the water. At that moment, something clicked in me and I felt a connection to everything. And then, in my mind's eye, I began seeing things; the beginning of the universe, the creation of galaxies, and the formation of our sun followed by the planets in our solar system. And then the earth started forming and life began to happen and I saw plants and trees being born and then disappear and the age of dinosaurs was a flash of light, disappearing into extinction. I was not thinking up to that point, just witnessing. Then I realized I was about to see the beginning of human history and that thought stopped it. I was outside of the moment with that thought and the moment ceased to exist. I sat there trying to understand what had just happened to me until I realized the sun was down and I was cold.

I started wondering over the next few days if what I saw was similar to what religious figures throughout history saw? And if so, would it be possible to get to that place again and continue the viewing time? I wondered if I could get back to that moment through the act of painting, because wasn't art really about seeing just beyond our realm of perceived reality?"

A Sainted Hunger, oil on canvas, 84 x 66", 1998

In 2009, Guffogg began a series of paintings called, At the Still Point of the Turning World, adapted from a T. S. Eliot poem, Four Quartets – Burnt Norton. These paintings explore the desire to find one’s center, to feel grounded or to connect back to one’s self. Guffogg began reading the poem many years before, but due to some personal life changes that were underfoot, he went back to the poem for solace. The connection he felt from the words began to resonate within him, and he realized that he needed to see his personal still point, thus beginning the series. The paintings are made up of a single line that loops back towards the center, over and over, until a seemingly infinite number of lines are overlaid, creating a deep space within a 2-dimensional surface. This “space” is conceptual and is solely created out of the act of being in that moment and moving his brush in a circular direction, with the limitations being only that of his own physicality. The paintings are a form of mediation for Guffogg, encompassing a mental and physical exercise to remember to be still. I find this work particularly compelling after reading Henry Miller’s, Stand Still Like the Hummingbird, as the depth of Guffogg’s work reaches within to awaken the inner-self, to realize one's true potential and meaning in life.

At the Still Point #33, oil on canvas, 60 x 60", 2010

At the Still Point of Turning World - Into the Rose Garden, oil on canvas, 60 x 48" 2016

After focusing on his inner still point for 2 years, in 2011 he began looking closely at Leonardo's portrait of Ginevra da Benci. Guffogg absorbed Da Vinci's portrait of the young woman and applied his newly found stillness to a visual conversation he wanted to have with Leonardo by taking the lines, shapes, and colors and weaving them into a series of abstract paintings. After all, Guffogg says he is a realist painter and abstraction is his subject matter. Within the context of the Ginevra series, I understand! The artist went on to paint over fifty abstract portraits, of various dimensions, that focus on bringing the essence of the flesh into visual thought and conscious form. This reinterpretation of flesh led to the use of a wide, paint-soaked brush so that his hand pulling it across the canvas would leave a mark that he said was more about the human form, as it was more of a direct link to his own physicality. Often, when he paints back into this spontaneous gestural moment, he paints the lines as if they are human skin that is twisting and turning in and around each other, like lovers embracing. They are sometimes sexually charged, but also organic, seemingly made up of random thoughts that have manifested from the ether and have come up to the surface; as if the canvas is a portal made up of a pool of different hued water for us to look into.

Leonardo da Vinci, Ginevra de Benci, oil on panel, 1474

Shane Guffogg, Ginevra de Benci #13, oil on canvas, 30 x 24", 2011

In 2014, Guffogg stretched up a large canvas measuring 96” x 108” and began working on a new painting that he felt was going to be a defining moment. The canvas took up the entire wall of his small Hollywood studio, and there was little room to stand back and take it all in. At one point while working on this painting, he wrote on a scrap piece of paper, “My conversation with God.” I asked him about it and he said that he felt that that was what he was doing with this painting – conversing with God. But the language was pure and unspoken, and it was all-encompassing for him. The painting went through many phases as the ribbons went from pale blues that were pushing into and floating over the alizarin crimson reds, to soft flesh tones, thus leaving the blues to be submerged in the underpainting. Guffogg worked on the painting for months until he reached a point where he felt that his wordless dialogue had been realized. He told me that he decided to end his 10 hour day of painting with a glass of wine to begin his decompression, which I connected to a kind of communion. He decided to go back into the studio and sit in the corner chair, the furthest point from the painting, to look at it, and observe it in its entirety. He felt that the painting was observing him as much as he was observing it. As he looked, he began to see lines that were going from side to side, as if a string was pulled across the length of the painting and gravity was weighing it down in the middle, creating an inverted arch. He realized that the line wasn't actually in the painting, but more lines began to appear.

The Observer is the Observed, oil on canvas, 96 x 108" 2014-2015

photographed outside the artist's studio

He was seeing what hadn't yet been painted and that the painting wasn't finished. He decided not to add the lines in that moment though, for fear that if he made a mistake, it would dry overnight and the painting would become lost. He waited until the next morning and went in, with his coffee in hand, and sat in the same chair: the lines again appeared. He searched his studio and found a long piece of ribbon, which he then pinned onto the sides of the canvas, to let gravity gentle pull the center down. He followed the line with a small brush several times, adding to the length of the ribbon each time so that the arches would be moving in unison. The following day, after the paint had dried, he went back into the new ribbons and added shadows and highlights so that they were interwoven throughout the piece. The spontaneous movements that began the painting now had a substructure, creating a balance between chaos and order. Rather than naming it after his divinely inspired scrap of paper, Guffogg titled it The Observer is the Observed, due to the potent experience he had had in creating it.

I stood still in front of the finished painting in his studio, surrendering, thawing; the ribbons embraced my being, caressing my mind; air rushed through, light soothed, and for a moment or so, I was one within the vacuum of my being. I awoke from this moment and asked myself, is this enlightenment?

The philosopher, writer, and speaker, J. Krishnamurti, once said,

“Your mind is a constant traffic of parts. It is complex to understand because the intellect is dialectical and dualistic. The knower must be separate from the known and it is impossible to comprehend, but through mysticism and letting go of thyself it can be realized, as mysticism does not agree with science, it goes beyond it. Mystery will never fall from the presence on the intellect, as it is our nature to evolve and discover ourselves and the world around us.

Meditation is watching the movement of thoughts in the mirror. Just be an Observer, as you are standing at the side of the road, no judgment, no evaluation, no condemnation, no appreciation, just pure observation, as you become more accustomed of observation, a strange phenomenon starts happening."

Guffogg painted his piece, The Observer is the Observed, in such a way that when the viewer stands in front of it, it is the viewer’s own eyesight that is illuminating the painting, and it is through the viewer's conscious awareness of that moment, that the painting is illuminated. This painting’s title became, as well, the title of his current retrospective. When the exhibition reached The Imperial Museum of Fine Arts, in St. Petersburg, Russian viewers went back after viewing hours and practiced yoga and meditation alongside it.

Stay tuned for Part 2

Victoria Chapman - Guffogg Studio

A viewer soaking up the light within

The Imperial Museum of Fine Arts Museum, St. Petersburg Russia